On a recent episode of The Weekly Show Podcast, Jon Stewart went after Senate Democrats. Hard. Frustrated by their vote on a continuing resolution to avert a government shutdown, he accused the entire Democratic caucus of staging political theater:

“Every single one [who voted for cloture] is not up for re-election in 2026, or retiring, which says to me that they put on a play... They just fucking didn’t [filibuster]... We don’t even know what they actually think, because they put on a play.”

That’s a strong charge — but it’s also an empirical question. Is there evidence that Senate Democrats coordinated to shield vulnerable members from political blowback?

I ran the numbers. Here’s what I found.

The Vote That Sparked It

In March 2025, Congress narrowly averted a government shutdown. A cloture vote in the Senate — requiring 60 votes — passed with just enough support. Ten Democrats (including Independents who caucus with them) voted “yes” to invoke cloture, enabling the Republican-led spending package to move forward:

Catherine Cortez Masto, Dick Durbin, John Fetterman, Kirsten Gillibrand, Maggie Hassan, Angus King (I), Gary Peters, Brian Schatz, Chuck Schumer, and Jeanne Shaheen.

The rest of the Democratic caucus — including Bernie Sanders (I) — voted “no.”

At first glance, this looked like a party split. But Stewart suggested something subtler: maybe Democratic leadership allowed only electorally safe members to vote yes, shielding those up for re-election in 2026.

That’s testable.

The Hypothesis

If Stewart's intuition is right, we should see a systematic pattern: Democrats who are electorally vulnerable should be less likely to vote yes on cloture.

To test this, I classified each Democratic senator (including Independents who caucus with them) as either: Vulnerable: up for re-election in 2026. Safe: not up in 2026, or retiring.

Of the Democrats facing re-election in 2026, Senators Gary Peters (MI), Jeanne Shaheen (NH), and Tina Smith (MN) have already announced they won't run, while Dick Durbin (IL) is widely expected to step down.

The remaining Democrats up in 2026 — including Senators Hickenlooper (CO), Coons (DE), Ossoff (GA), Markey (MA), Booker (NJ), Luján (NM), Merkley (OR), Reed (RI), and Warner (VA) — are vulnerable to potential primary challenges and the general election.

These vulnerable senators span the ideological spectrum of the Democratic caucus, from progressives like Ed Markey (MA) and Jeff Merkley (OR) to moderates like Mark Warner (VA) and John Hickenlooper (CO). Some represent relatively safe Democratic states like Massachusetts; others more competitive states like Georgia.

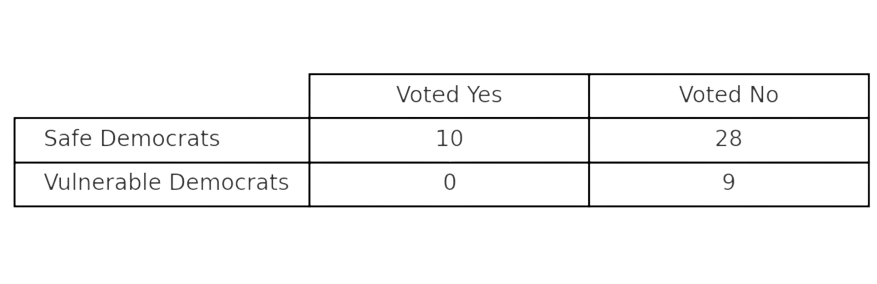

Here’s the 2x2 table:

No vulnerable Democrats voted yes. Not one.

This isn’t random. It’s directional.

And it doesn’t appear to be ideological. The group of vulnerable Democrats includes both liberal firebrands and centrists. Some represent relatively safe Democratic states like Massachusetts; others hold seats in more competitive states like Georgia. What unites them isn’t policy or ideology — it’s position.

When a full bloc of senators facing reelection all make the same call, while their safer colleagues split their votes, the pattern speaks for itself. You don’t need a p-value to see the gravity.

So what does it mean?

While it's clear the pattern isn't random, the motive is murkier. Two plausible explanations emerge:

Self-protection: vulnerable senators independently voted “no” to guard their reputations.

Coordinated protection: leadership assigned “yes” votes to safe members, shielding colleagues who couldn't afford to support the bill.

The distinction matters. The first explanation suggests fecklessness. The second points to a collective strategic response to electoral risk — one that aims to make an unpopular decision while maintaining plausible deniability.

Here the evidence is suggestive: two of the “yes” votes came from senators not seeking reelection in 2026—Peters and Shaheen—which points toward coordination.

Why This Matters

This isn’t just about a single vote. It’s a window into how political parties manage vulnerability under pressure.

In that light, fecklessness and strategic coordination aren’t opposites—they’re often the same impulse: to prioritize institutional preservation and member survival over policy coherence, ideology or public transparency.

The fact that not one vulnerable Democrat voted yes raises hard questions. Was it spontaneous caution? Or a calculated maneuver to avoid electoral risk?

And if party leaders anticipated the backlash—and moved to contain it—what does that reveal about their assumptions, not just about voters, but about what the party base truly expects of them?

So... Was It a Staged Play?

It certainly looked choreographed. But what kind of play was it? A tragedy? A farce? A strategic improvisation?

What frustrates observers like Stewart may not just be the vote itself, but the opacity. The Senate operates in a fog of symbolism. Votes like this blur the line between conviction and calculation.

Is that corruption? Or is it just realism in an age of asymmetric polarization, where survival outweighs principles?

Final Takeaway

Stewart saw theater. The numbers show strategy. But what kind of strategy?

In shielding their most vulnerable members, Senate Democrats may have protected themselves—but at a cost.

Not just in optics. Not just in authenticity. But in the kind of opposition the country needs.

A democracy under threat demands clarity, conviction, and renewal. But the tactics of self-preservation—no matter how rational—tend to entrench incumbency and delay generational change.

It’s that the party keeps preserving itself—at the expense of becoming something better, and what the moment demands.

If you found this analysis useful, share it. Or tell me what I missed. Debate sharpens the point.

Subscribe for more data-driven dives into the gap between what politicians do — and why they do it.

March 2025